Copy to clipboard

Copy to clipboard

In anticipation of the NASS Annual Meeting, we have been asked to share our perspective on the spine specialty today, especially for the nexus of care stakeholders: hospitals and Integrated Delivery Networks (IDNs), physician specialists and device manufacturers/OEMs. This is a diverse group, though one with overlapping interests.

While back pain remains one of the most common conditions treated by physicians, unfortunately the prevailing model for the delivery of spine services is often archaic, with discreet and siloed services lacking rapid access, care integration and a focus on an exceptional patient experience.

Healthcare, specifically the spine and orthopaedic specialties, is experiencing a period of extended and dramatic change driven largely by hospital consolidation into systems (IDNs), along with new models of reimbursement, novel technology, increased hospital/physician alignment and a heightened focus on demonstrable clinical quality. And with an aging population and increasing prevalence of musculoskeletal pathologies for patients of all ages, spine is among the most attractive among service offerings to develop for both medical centers and community-based settings.

One of the most important and beneficial effects of these industry changes is the emergence of deliberate efforts by hospitals to collaborate with their medical staff. In practice, this translates to the management and delivery of the core elements of care (clinical outcomes, operational efficiency and financial performance) migrating away from hospitals and physicians working independently, and sometimes at cross purposes, toward increased collaboration for the benefit of all stakeholders, including the patient. Overall, we view such collaboration as foundational to the success of a spine program. Without aligned goals among providers, spine programs will not achieve three critical goals of growth, quality and differentiation.

How should this collaboration be accomplished?

While fee-for-service reimbursement remains the dominant model, payment is steadily moving to value-based models such as bundling, total episode-of-care payment, capitation and other fixed-fee arrangements. One gap we often encounter is the paucity of data for driving strategy, decision-making and service redesign. While most organizations collect the data, Corazon believes that this information is typically not organized and distributed in ways that leverage its value for case review, performance improvement or other benefits to the service line. Simply collecting the data won’t benefit the program in any way; this information must be analyzed and then shared to have an impact on future practice. Expanded data reporting is essential and is fast becoming a requirement.

Clinical and Functional Outcomes to Substantiate Effectiveness

As a subset of broader data collection, consider functional outcomes: does the patient get better as evidenced by less pain, more mobility, improved quality of life, a return to work and other individual milestones? When conducting assessments, we routinely ask medical and hospital staffs what data is collected for functional outcomes. While virtually every hospital and physician acknowledges that they should collect outcomes data, very few actually do…and even fewer use this information for performance improvement. Meanwhile, physicians typically believe that they have high patient satisfaction, but without clear knowledge of data to support this claim.

John Pracyk, M.D., Ph.D., MBA, a neurological surgeon and Worldwide Integrated Leader of Medical Affairs and Pre-Clinical & Clinical Research at DePuy Synthes Spine, coined the term “Surgical Meritocracy” to denote a new culture of comparative measurement. Because consistent and broadly-based outcomes have not been routinely collected, many surgeons are naturally skeptical of the means and uses of such data. His experience was that measurement precedes understanding and provides a genuine basis for improving care while (equally importantly) substantiating value. According to Dr. Pracyk, “The surgeon may believe they are good, but does someone who is paying for care and the patient believe they are good?”

Beyond the development and sporadic use of standard assessment tools, surprisingly little has been done to bring measures of effectiveness to the clinical practice of spine care on a national scale in the U.S. This will certainly change as valued-base reimbursement requires evidence of quality outcomes. Moreover, collection, reporting and application of operational, clinical, coupled with functional outcomes data will emerge as a primary driver for contracting, while simultaneously becoming a source of comparative effectiveness data for both physicians and hospitals.

Setting Priorities

From Corazon’s U.S. perspective, looking across hundreds of spine providers, there are a number of key mid- to long-term priorities that will benefit health systems, physicians, OEMs and consumers. While identifying and managing these multiple and shifting priorities can be daunting, positive programmatic results can be achieved with attention to overall strategy and tactical details of spine services.

Organized by group, these priorities include:

Health Systems

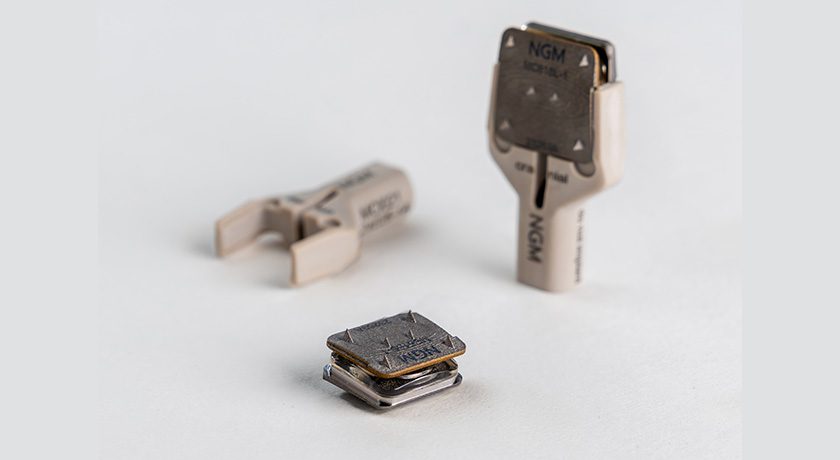

- Maintaining financial viability and managing cost. As providers evaluate the cost of spine care, especially for surgical spine, the implant can sometimes be the most costly element of care, which requires close attention and negotiation.

- Strategically and proactively navigating the shift to the ambulatory settings.

- Seeking commercial and CMS-bundled payment contracting opportunities.

- Aligning with physicians, whether private or employed, through program leadership roles, co-management, gainsharing, bundled payment, Clinically Integrated Networks and other means.

- Collecting and reporting quality and functional metrics that will meaningfully measure clinical, functional and operational performance.

- Growing market share through the expansion of primary and specialty care referral bases (owned or in partnership) and community-based services that provide rapid access and patient engagement.

Physicians

- Evaluating clinical and business alliances that retain and grow referral networks.

- Seeking and committing to opportunities to lead, develop, and manage spine care across a spectrum of locations (e.g., surgical and non-surgical, hospital- and community-based, etc.).

- Exploring opportunities to align with health systems such as Management Services Agreements, Professional Services Agreements, program leadership, co-management, gainsharing and other models.

- Pursuing professional alliances such as chiropractic and other alternative and complementary treatments that represent reciprocal referral bases.

- Collecting, measuring and reporting patient functional outcomes as a means to differentiate care and substantiate quality claims.

- Assertively investigating commercial bundled payment opportunities.

OEMs

- Seeking a deep understanding of hospital systems of care and how their product “lives” in the provider and patient “use cycle” (from implantation through return to function and quality of life).

- Wearing the “buyer’s hat” to understand price, value, outcomes and service.

- Exploring flexible pricing approaches that might include bundled pricing, place of service pricing (hospital, ASC, population health), outcomes-based pricing, value-added support services, etc.

- Pursuing collaborative, long-term relationships with IDNs and physicians.

- Exploring the collection and reporting of implant-related functional data to identify devices and procedures that result in better patient outcomes. OEMs that can support price with value or improved quality will be more advantageously positioned.

In Focus: OEMs

Historically, from the hospital’s perspective, manufacturers primarily courted physicians while the hospital paid the bill, even as reimbursement declined. In some cases, this has engendered lingering distrust among hospital leadership, surgeons and OEMs. While the surgeon remains an OEM customer, market forces are increasingly expanding the customer base to include hospital executives, regional and national decision-makers and payors, mostly due to these other parties’ influence and interest in a strengthened value analysis processes for equipment and devices.

Moreover, newer reimbursement models and cost containment initiatives that reward physicians (bundled payment, gainsharing, co-management, etc.) are challenging implant brand allegiance and well-established relationships with manufacturers, potentially shifting surgeon and hospital loyalties in favor of others who will bring greater value or patient benefit or both.

Without a full understanding of a product’s use cycle, OEMs tend to see their product as a primary element, while providers see the product as one of many. We believe that OEMs have an opportunity to grow market share, but not without knowledge of unique provider environments, as well as a fluency in the overall culture and language of providers. This remains an opportunity for providers to negotiate pricing and begin to develop new relationships, whereas previously they may have felt “stuck” in a long-term relationship that was no longer bringing value in one way or another.

Additionally, an extension of use cycle may be “design thinking,” first pioneered in the Stanford School of Design and applied across many industries, healthcare included. Their “deep dive” approach may have applicability to innovating the vendor/provider space by granular process deconstruction and redesign of the multitude of variables in spine care continuums. A corollary to this process was described in 2013 as “provider modeling,” which envisioned a process of reciprocal research, uncovering latent needs and generating new insights. This type of redesign will require an intentional focus and approaching a broader provider audience with a compelling commitment to a plan of engagement.

Much like providers tend to live in “two worlds”—fee-for-service and value-based care—OEMs should not only operate in traditional sales and support roles, but also in strategic ones; perhaps migrating to holistic solutions that align with provider realities and cost and clinical outcomes. One suggested approach comes from Alok Sharan, M.D., WestMed Spine Center Co-Director and Corazon Spine Medical Advisor. Dr. Sharan suggests that OEMs consider the development of site-specific business models (including pricing and support services) that align with customer business models in the inpatient, ASC, bundled payment and population health settings. Corazon believes that this model could create competitive advantage for OEMs.

Comprehensive Spine

Industry dynamism has led to renewed interest in the spine service line, especially in the development of comprehensive services (surgical and nonsurgical spine) as a viable strategy to lead with ancillary services such as rehabilitation, pain management and imaging into a broader system of integrated back and neck care.

Historically, many hospitals have been surgically focused due to attractive profit margins. Recognizing that 90% of patients with back pain will NOT be surgical candidates, health systems and providers are starting to acknowledge that they must strategically lead with non-surgical services as a means to complement surgical spine. For many systems, this represents a substantial reset of thinking and therefore, requires a reorganization of resources, especially in community-based and ASC settings.

Intake and Triage Systems

In multiple conversations with surgeons, “reverse triage” has become more prevalent, and also ineffective. Reverse triage occurs when surgeons are the first line provider for primary care physician referral. Too often, after initial evaluation, the surgeon concludes that the patient is not a surgical candidate and refers her to more appropriate non-surgical care. This frustrates not only the patient, but also the referring physician and surgeon, and lengthens the wait time for evaluation and subsequent treatment. Reverse triage is symptomatic of inadequate systems of intake, and triage and should be tracked so the initial interaction of the patient with care is as effective as possible from the outset.

Several key elements are essential to attract and retain referring professionals and patients for non-surgical volume: rapid patient access, expedited triage to the most appropriate clinical provider and patient navigation through both the clinical and administrative elements of care. Almost without exception, Corazon has found that the outmigration of spine patients to competitive providers is a common problem. These cases are most often lost to competitors when 1) referral sources and self-referred patients encounter extended waits to see a spine professional, or 2) there is a perception that better and more sophisticated care is being offered elsewhere. The first is an access problem, while the second is an educational and marketing problem. As noted above, effective systems of intake will address patient access. The most effective defense against perceptions of quality is a combination of a robust educational campaign to referring professionals and patients, coupled with presentation of functional outcomes data to both audiences.

With the highly dynamic nature and complexities of healthcare, especially in the spine specialty as outlined above, it is likely that new models of hospital-OEM-provider collaborations will emerge from highly-focused pilots. We recommend starting with small teams, clear and focused objectives, and goals to course correct rapidly while avoiding premature and untested deployment of solutions and initiatives. Organizations that aggressively pursue new collaborative models for not only device marketing and sales, but also physician interaction, will be best positioned to strategically excel in anticipating and leveraging changes in the spine specialty today and into the future.

The future for spine care is bright, but will require strategically rethinking traditional business practices with a greater emphasis on collaboration and more intimately understanding the respective products, services and goals for each stakeholder: providers, physicians and OEMs.

In anticipation of the NASS Annual Meeting, we have been asked to share our perspective on the spine specialty today, especially for the nexus of care stakeholders: hospitals and Integrated Delivery Networks (IDNs), physician specialists and device manufacturers/OEMs. This is a diverse group, though one with overlapping interests.

While back...

In anticipation of the NASS Annual Meeting, we have been asked to share our perspective on the spine specialty today, especially for the nexus of care stakeholders: hospitals and Integrated Delivery Networks (IDNs), physician specialists and device manufacturers/OEMs. This is a diverse group, though one with overlapping interests.

While back pain remains one of the most common conditions treated by physicians, unfortunately the prevailing model for the delivery of spine services is often archaic, with discreet and siloed services lacking rapid access, care integration and a focus on an exceptional patient experience.

Healthcare, specifically the spine and orthopaedic specialties, is experiencing a period of extended and dramatic change driven largely by hospital consolidation into systems (IDNs), along with new models of reimbursement, novel technology, increased hospital/physician alignment and a heightened focus on demonstrable clinical quality. And with an aging population and increasing prevalence of musculoskeletal pathologies for patients of all ages, spine is among the most attractive among service offerings to develop for both medical centers and community-based settings.

One of the most important and beneficial effects of these industry changes is the emergence of deliberate efforts by hospitals to collaborate with their medical staff. In practice, this translates to the management and delivery of the core elements of care (clinical outcomes, operational efficiency and financial performance) migrating away from hospitals and physicians working independently, and sometimes at cross purposes, toward increased collaboration for the benefit of all stakeholders, including the patient. Overall, we view such collaboration as foundational to the success of a spine program. Without aligned goals among providers, spine programs will not achieve three critical goals of growth, quality and differentiation.

How should this collaboration be accomplished?

While fee-for-service reimbursement remains the dominant model, payment is steadily moving to value-based models such as bundling, total episode-of-care payment, capitation and other fixed-fee arrangements. One gap we often encounter is the paucity of data for driving strategy, decision-making and service redesign. While most organizations collect the data, Corazon believes that this information is typically not organized and distributed in ways that leverage its value for case review, performance improvement or other benefits to the service line. Simply collecting the data won’t benefit the program in any way; this information must be analyzed and then shared to have an impact on future practice. Expanded data reporting is essential and is fast becoming a requirement.

Clinical and Functional Outcomes to Substantiate Effectiveness

As a subset of broader data collection, consider functional outcomes: does the patient get better as evidenced by less pain, more mobility, improved quality of life, a return to work and other individual milestones? When conducting assessments, we routinely ask medical and hospital staffs what data is collected for functional outcomes. While virtually every hospital and physician acknowledges that they should collect outcomes data, very few actually do…and even fewer use this information for performance improvement. Meanwhile, physicians typically believe that they have high patient satisfaction, but without clear knowledge of data to support this claim.

John Pracyk, M.D., Ph.D., MBA, a neurological surgeon and Worldwide Integrated Leader of Medical Affairs and Pre-Clinical & Clinical Research at DePuy Synthes Spine, coined the term “Surgical Meritocracy” to denote a new culture of comparative measurement. Because consistent and broadly-based outcomes have not been routinely collected, many surgeons are naturally skeptical of the means and uses of such data. His experience was that measurement precedes understanding and provides a genuine basis for improving care while (equally importantly) substantiating value. According to Dr. Pracyk, “The surgeon may believe they are good, but does someone who is paying for care and the patient believe they are good?”

Beyond the development and sporadic use of standard assessment tools, surprisingly little has been done to bring measures of effectiveness to the clinical practice of spine care on a national scale in the U.S. This will certainly change as valued-base reimbursement requires evidence of quality outcomes. Moreover, collection, reporting and application of operational, clinical, coupled with functional outcomes data will emerge as a primary driver for contracting, while simultaneously becoming a source of comparative effectiveness data for both physicians and hospitals.

Setting Priorities

From Corazon’s U.S. perspective, looking across hundreds of spine providers, there are a number of key mid- to long-term priorities that will benefit health systems, physicians, OEMs and consumers. While identifying and managing these multiple and shifting priorities can be daunting, positive programmatic results can be achieved with attention to overall strategy and tactical details of spine services.

Organized by group, these priorities include:

Health Systems

- Maintaining financial viability and managing cost. As providers evaluate the cost of spine care, especially for surgical spine, the implant can sometimes be the most costly element of care, which requires close attention and negotiation.

- Strategically and proactively navigating the shift to the ambulatory settings.

- Seeking commercial and CMS-bundled payment contracting opportunities.

- Aligning with physicians, whether private or employed, through program leadership roles, co-management, gainsharing, bundled payment, Clinically Integrated Networks and other means.

- Collecting and reporting quality and functional metrics that will meaningfully measure clinical, functional and operational performance.

- Growing market share through the expansion of primary and specialty care referral bases (owned or in partnership) and community-based services that provide rapid access and patient engagement.

Physicians

- Evaluating clinical and business alliances that retain and grow referral networks.

- Seeking and committing to opportunities to lead, develop, and manage spine care across a spectrum of locations (e.g., surgical and non-surgical, hospital- and community-based, etc.).

- Exploring opportunities to align with health systems such as Management Services Agreements, Professional Services Agreements, program leadership, co-management, gainsharing and other models.

- Pursuing professional alliances such as chiropractic and other alternative and complementary treatments that represent reciprocal referral bases.

- Collecting, measuring and reporting patient functional outcomes as a means to differentiate care and substantiate quality claims.

- Assertively investigating commercial bundled payment opportunities.

OEMs

- Seeking a deep understanding of hospital systems of care and how their product “lives” in the provider and patient “use cycle” (from implantation through return to function and quality of life).

- Wearing the “buyer’s hat” to understand price, value, outcomes and service.

- Exploring flexible pricing approaches that might include bundled pricing, place of service pricing (hospital, ASC, population health), outcomes-based pricing, value-added support services, etc.

- Pursuing collaborative, long-term relationships with IDNs and physicians.

- Exploring the collection and reporting of implant-related functional data to identify devices and procedures that result in better patient outcomes. OEMs that can support price with value or improved quality will be more advantageously positioned.

In Focus: OEMs

Historically, from the hospital’s perspective, manufacturers primarily courted physicians while the hospital paid the bill, even as reimbursement declined. In some cases, this has engendered lingering distrust among hospital leadership, surgeons and OEMs. While the surgeon remains an OEM customer, market forces are increasingly expanding the customer base to include hospital executives, regional and national decision-makers and payors, mostly due to these other parties’ influence and interest in a strengthened value analysis processes for equipment and devices.

Moreover, newer reimbursement models and cost containment initiatives that reward physicians (bundled payment, gainsharing, co-management, etc.) are challenging implant brand allegiance and well-established relationships with manufacturers, potentially shifting surgeon and hospital loyalties in favor of others who will bring greater value or patient benefit or both.

Without a full understanding of a product’s use cycle, OEMs tend to see their product as a primary element, while providers see the product as one of many. We believe that OEMs have an opportunity to grow market share, but not without knowledge of unique provider environments, as well as a fluency in the overall culture and language of providers. This remains an opportunity for providers to negotiate pricing and begin to develop new relationships, whereas previously they may have felt “stuck” in a long-term relationship that was no longer bringing value in one way or another.

Additionally, an extension of use cycle may be “design thinking,” first pioneered in the Stanford School of Design and applied across many industries, healthcare included. Their “deep dive” approach may have applicability to innovating the vendor/provider space by granular process deconstruction and redesign of the multitude of variables in spine care continuums. A corollary to this process was described in 2013 as “provider modeling,” which envisioned a process of reciprocal research, uncovering latent needs and generating new insights. This type of redesign will require an intentional focus and approaching a broader provider audience with a compelling commitment to a plan of engagement.

Much like providers tend to live in “two worlds”—fee-for-service and value-based care—OEMs should not only operate in traditional sales and support roles, but also in strategic ones; perhaps migrating to holistic solutions that align with provider realities and cost and clinical outcomes. One suggested approach comes from Alok Sharan, M.D., WestMed Spine Center Co-Director and Corazon Spine Medical Advisor. Dr. Sharan suggests that OEMs consider the development of site-specific business models (including pricing and support services) that align with customer business models in the inpatient, ASC, bundled payment and population health settings. Corazon believes that this model could create competitive advantage for OEMs.

Comprehensive Spine

Industry dynamism has led to renewed interest in the spine service line, especially in the development of comprehensive services (surgical and nonsurgical spine) as a viable strategy to lead with ancillary services such as rehabilitation, pain management and imaging into a broader system of integrated back and neck care.

Historically, many hospitals have been surgically focused due to attractive profit margins. Recognizing that 90% of patients with back pain will NOT be surgical candidates, health systems and providers are starting to acknowledge that they must strategically lead with non-surgical services as a means to complement surgical spine. For many systems, this represents a substantial reset of thinking and therefore, requires a reorganization of resources, especially in community-based and ASC settings.

Intake and Triage Systems

In multiple conversations with surgeons, “reverse triage” has become more prevalent, and also ineffective. Reverse triage occurs when surgeons are the first line provider for primary care physician referral. Too often, after initial evaluation, the surgeon concludes that the patient is not a surgical candidate and refers her to more appropriate non-surgical care. This frustrates not only the patient, but also the referring physician and surgeon, and lengthens the wait time for evaluation and subsequent treatment. Reverse triage is symptomatic of inadequate systems of intake, and triage and should be tracked so the initial interaction of the patient with care is as effective as possible from the outset.

Several key elements are essential to attract and retain referring professionals and patients for non-surgical volume: rapid patient access, expedited triage to the most appropriate clinical provider and patient navigation through both the clinical and administrative elements of care. Almost without exception, Corazon has found that the outmigration of spine patients to competitive providers is a common problem. These cases are most often lost to competitors when 1) referral sources and self-referred patients encounter extended waits to see a spine professional, or 2) there is a perception that better and more sophisticated care is being offered elsewhere. The first is an access problem, while the second is an educational and marketing problem. As noted above, effective systems of intake will address patient access. The most effective defense against perceptions of quality is a combination of a robust educational campaign to referring professionals and patients, coupled with presentation of functional outcomes data to both audiences.

With the highly dynamic nature and complexities of healthcare, especially in the spine specialty as outlined above, it is likely that new models of hospital-OEM-provider collaborations will emerge from highly-focused pilots. We recommend starting with small teams, clear and focused objectives, and goals to course correct rapidly while avoiding premature and untested deployment of solutions and initiatives. Organizations that aggressively pursue new collaborative models for not only device marketing and sales, but also physician interaction, will be best positioned to strategically excel in anticipating and leveraging changes in the spine specialty today and into the future.

The future for spine care is bright, but will require strategically rethinking traditional business practices with a greater emphasis on collaboration and more intimately understanding the respective products, services and goals for each stakeholder: providers, physicians and OEMs.

You are out of free articles for this month

Subscribe as a Guest for $0 and unlock a total of 5 articles per month.

You are out of five articles for this month

Subscribe as an Executive Member for access to unlimited articles, THE ORTHOPAEDIC INDUSTRY ANNUAL REPORT and more.

PV

Patrick Vega is Consulting Director for Vizient’s Excelerate and PPI Orthopedics. Mr. Vega consults to member hospitals, health systems and physicians in musculoskeletal services with a focus on high-value care by aligning cost, quality and performance.