Copy to clipboard

Copy to clipboard

While the spine industry has focused on 3D printed cages, enabling technology and minimally invasive surgery, it has forgotten a critical priority: infection prevention, says Aakash Agarwal, Ph.D., Director of Research at Spinal Balance. He argues that the millions of reprocessed and exposed orthopedic devices in the field should be a significant focus for the industry.

“Every upcoming technology in the field of orthopedics focuses on precision and efficacy, with the intention to boost performance (healing) and safety,” he said. “Avoiding reprocessing and intraoperative exposure is the most obvious (and also most neglected) safety measure in the orthopedic industry. Fixing this problem will be a major leap toward patient safety.”

Dr. Agarwal has published multiple studies on the topic of surgical site infection (SSI), including soon-to-be-published level II clinical evidence on reducing bacterial transmission to patients by guarding the pedicle screws.

We asked Dr. Agarwal four questions about what his recent research found and ways to handle infections.

Can you tell us about your recent work on infection after instrumented spine surgery?

Dr. Agarwal: Infection after spine surgery happens at a rate higher than 10% and can occur up to three to five years after surgery. I am sure you haven’t heard this, because reimbursement policies and short-term studies only look at 30 to 90 days after surgery. In reality, post-operative infections could be divided into early-onset, delayed-onset and late-onset infection.

Most people, when they talk about infection, talk about early-onset infection, identified as occurring immediately after spine surgery, constituting up to 50% of all reported infections.

Delayed-onset infection occurs from 90 days to a year from the date of surgery, and constitutes between 15% and 35% of all reported infections.

Late-onset infection, which occurs after one year post-op, is the least studied infection type due to lack of long follow-up periods. However, the few longer-term studies that have been extended over six years have shown 56 to 80 months as the average SSI detection length. These infections account for 9.7% of total incidences.

What’s the occult infection phenomenon associated with orthopedic devices?

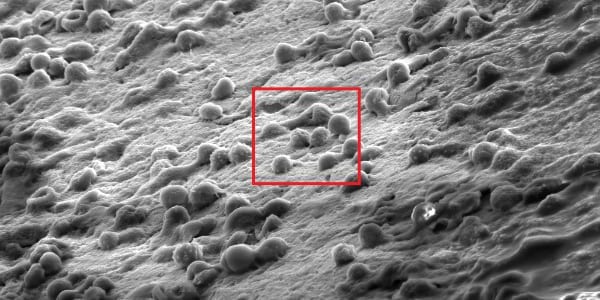

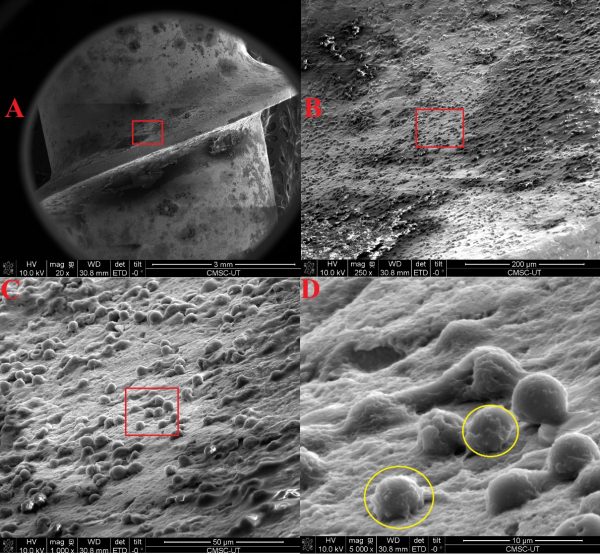

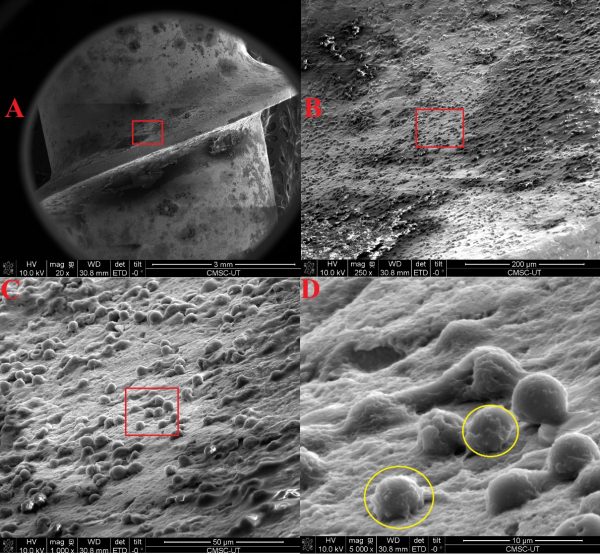

Dr. Agarwal: Clinical studies from multiple groups in the U.S. and Europe, including our ongoing trial [Figure 1], show that a significant number of patients undergoing revision surgery for loosened hardware have bacterial growth around the screw, with no known clinical symptoms of SSI.

Figure 1: Reprocessed and intraoperatively exposed implant removed from patient due to “aseptic” loosening showing biofilm.

To explain in brief, what’s happening with impregnated bacteria from contaminated implants is that they can lie dormant or can result in early infection. If they lie dormant, they continue to hide from our immune system and thrive via biofilm formation on the implant.

This biofilm can break, and the bacteria can cause delayed or late infection response at a later stage, which we already talked about. Now instead of systemic response, there could be a local response where the implant and the bone begin to disassociate, leading to screw loosening and failed fusion. This is what we have started to call an occult infection phenomenon. So, more reasons for us to keep the implants pristine.

You have been working extensively on clinical research to study orthopedic implant contamination. What have been some of your important findings?

Dr. Agarwal: I can divide my research work on this topic into two subcategories. First is repeated reprocessing and second is the exposure of implants, inside the sterile field, during spine surgery.

For repeated reprocessing, we found a variety of contaminants at the interfaces of the pedicle screws. These results are consistent with past literature and the reports received by the department of health in Scotland. And I already explained why it happens, which is, these devices have a lot of impervious features and aren’t built to be repeatedly reprocessed. In the second half of our study, we looked at the effect of exposure that these spinal implants undergo inside of the so-called “sterile” field. For this study, we ran a multi-center trial. We found that standard exposures that the orthopedic implants are undergoing always result in the accumulation of enough bacteria that leads colonies to form. In contrast, if we simply bypass exposure via a sterile sheath or a guard around these implants, then there was zero bacterial growth. This trial provided us with very strong clinical evidence that intraoperatively guarded (or unexposed) implants are devoid of any colony-forming bacteria, unlike the implants which were exposed.

In addition to our study, which established the precise mode of contamination, there are complementary studies where surgeons tried to reduce exposure of their implant by an elaborate means. For instance, in one study, they changed their gloves every time they accessed a new pedicle screw. Consequently, they reduced their infection rate by a measure of 70%. But this increases the effort required during surgery, only focuses on one type of exposure (e.g., touch) and, as it is process dependent, how do you make everybody compliant?

The take-home message of our study is to use a pre-sterile, pre-packaged implant, inside of which the implant should be housed in a guard or sheath, which would avoid microbial exposure in the sterile field during surgery.

Should implants be replaced if the infection happens at later stages (delayed- and late-onset)?

Dr. Agarwal: The conclusion of the study was to remove or replace implants for late-onset infection. Any attempt to retain the implant places the patient at high risk of recurrence of infection and biofilm growth. Considering the deleterious effect of long-term risk of infection and biofilm susceptibility of orthopedic implants, repeated reprocessing and intraoperative exposure of permanent implants, I would even recommend considering replacement of implants for delayed infection, perhaps a risk stratification approach based on patient’s comorbidities.

While the spine industry has focused on 3D printed cages, enabling technology and minimally invasive surgery, it has forgotten a critical priority: infection prevention, says Aakash Agarwal, Ph.D., Director of Research at Spinal Balance. He argues that the millions of reprocessed and exposed orthopedic devices in the field should be a significant...

While the spine industry has focused on 3D printed cages, enabling technology and minimally invasive surgery, it has forgotten a critical priority: infection prevention, says Aakash Agarwal, Ph.D., Director of Research at Spinal Balance. He argues that the millions of reprocessed and exposed orthopedic devices in the field should be a significant focus for the industry.

“Every upcoming technology in the field of orthopedics focuses on precision and efficacy, with the intention to boost performance (healing) and safety,” he said. “Avoiding reprocessing and intraoperative exposure is the most obvious (and also most neglected) safety measure in the orthopedic industry. Fixing this problem will be a major leap toward patient safety.”

Dr. Agarwal has published multiple studies on the topic of surgical site infection (SSI), including soon-to-be-published level II clinical evidence on reducing bacterial transmission to patients by guarding the pedicle screws.

We asked Dr. Agarwal four questions about what his recent research found and ways to handle infections.

Can you tell us about your recent work on infection after instrumented spine surgery?

Dr. Agarwal: Infection after spine surgery happens at a rate higher than 10% and can occur up to three to five years after surgery. I am sure you haven’t heard this, because reimbursement policies and short-term studies only look at 30 to 90 days after surgery. In reality, post-operative infections could be divided into early-onset, delayed-onset and late-onset infection.

Most people, when they talk about infection, talk about early-onset infection, identified as occurring immediately after spine surgery, constituting up to 50% of all reported infections.

Delayed-onset infection occurs from 90 days to a year from the date of surgery, and constitutes between 15% and 35% of all reported infections.

Late-onset infection, which occurs after one year post-op, is the least studied infection type due to lack of long follow-up periods. However, the few longer-term studies that have been extended over six years have shown 56 to 80 months as the average SSI detection length. These infections account for 9.7% of total incidences.

What’s the occult infection phenomenon associated with orthopedic devices?

Dr. Agarwal: Clinical studies from multiple groups in the U.S. and Europe, including our ongoing trial [Figure 1], show that a significant number of patients undergoing revision surgery for loosened hardware have bacterial growth around the screw, with no known clinical symptoms of SSI.

Figure 1: Reprocessed and intraoperatively exposed implant removed from patient due to “aseptic” loosening showing biofilm.

To explain in brief, what’s happening with impregnated bacteria from contaminated implants is that they can lie dormant or can result in early infection. If they lie dormant, they continue to hide from our immune system and thrive via biofilm formation on the implant.

This biofilm can break, and the bacteria can cause delayed or late infection response at a later stage, which we already talked about. Now instead of systemic response, there could be a local response where the implant and the bone begin to disassociate, leading to screw loosening and failed fusion. This is what we have started to call an occult infection phenomenon. So, more reasons for us to keep the implants pristine.

You have been working extensively on clinical research to study orthopedic implant contamination. What have been some of your important findings?

Dr. Agarwal: I can divide my research work on this topic into two subcategories. First is repeated reprocessing and second is the exposure of implants, inside the sterile field, during spine surgery.

For repeated reprocessing, we found a variety of contaminants at the interfaces of the pedicle screws. These results are consistent with past literature and the reports received by the department of health in Scotland. And I already explained why it happens, which is, these devices have a lot of impervious features and aren’t built to be repeatedly reprocessed. In the second half of our study, we looked at the effect of exposure that these spinal implants undergo inside of the so-called “sterile” field. For this study, we ran a multi-center trial. We found that standard exposures that the orthopedic implants are undergoing always result in the accumulation of enough bacteria that leads colonies to form. In contrast, if we simply bypass exposure via a sterile sheath or a guard around these implants, then there was zero bacterial growth. This trial provided us with very strong clinical evidence that intraoperatively guarded (or unexposed) implants are devoid of any colony-forming bacteria, unlike the implants which were exposed.

In addition to our study, which established the precise mode of contamination, there are complementary studies where surgeons tried to reduce exposure of their implant by an elaborate means. For instance, in one study, they changed their gloves every time they accessed a new pedicle screw. Consequently, they reduced their infection rate by a measure of 70%. But this increases the effort required during surgery, only focuses on one type of exposure (e.g., touch) and, as it is process dependent, how do you make everybody compliant?

The take-home message of our study is to use a pre-sterile, pre-packaged implant, inside of which the implant should be housed in a guard or sheath, which would avoid microbial exposure in the sterile field during surgery.

Should implants be replaced if the infection happens at later stages (delayed- and late-onset)?

Dr. Agarwal: The conclusion of the study was to remove or replace implants for late-onset infection. Any attempt to retain the implant places the patient at high risk of recurrence of infection and biofilm growth. Considering the deleterious effect of long-term risk of infection and biofilm susceptibility of orthopedic implants, repeated reprocessing and intraoperative exposure of permanent implants, I would even recommend considering replacement of implants for delayed infection, perhaps a risk stratification approach based on patient’s comorbidities.

You are out of free articles for this month

Subscribe as a Guest for $0 and unlock a total of 5 articles per month.

You are out of five articles for this month

Subscribe as an Executive Member for access to unlimited articles, THE ORTHOPAEDIC INDUSTRY ANNUAL REPORT and more.

CL

Carolyn LaWell is ORTHOWORLD's Chief Content Officer. She joined ORTHOWORLD in 2012 to oversee its editorial and industry education. She previously served in editor roles at B2B magazines and newspapers.