Copy to clipboard

Copy to clipboard

Cartilage repair and replacement is an underserved niche in the sports medicine market that could provide substantial opportunity for newcomers. Nanochon is one startup that plans to target the market with an off-the-shelf 3D-printed biomaterial device.

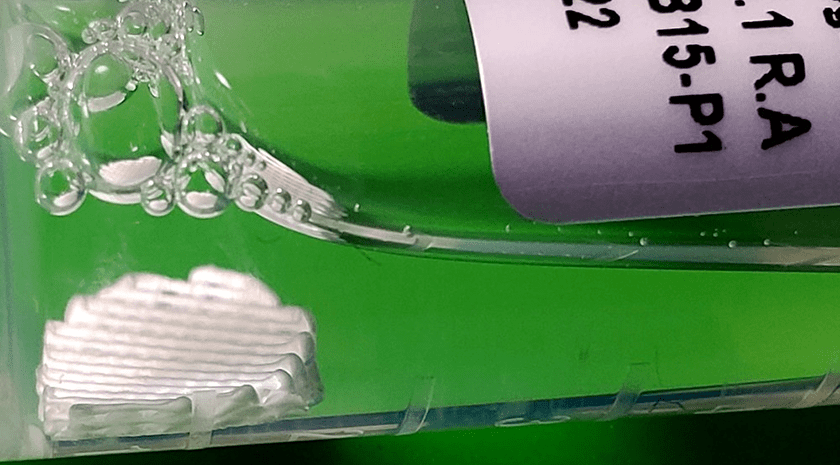

Nanochon describes its Chondrograft as “a sturdy medical advancement that is one part orthopedic load-bearing implant, one part tissue growth scaffold and completely revolutionary.” The company is focused on developing a nylon-based 3D-printed implant that easily integrates into a surgeon’s workflow without adding steps like cell seeding.

“We’re estimating a $2 billion target market in the U.S. annually, specifically for the sports medicine application,” said Benjamin Holmes, Ph.D., CEO of Nanochon. He noted the company is targeting younger, more active patients with knee cartilage damage or degeneration.

Dr. Holmes and CTO Nathan Castro, Ph.D., co-founded Nanochon in 2016. Their Chondrograft is an FDA premarket approval (PMA) device, with which they hope to bring to market in 2027.

We spoke with Dr. Holmes about Nanochon’s technology, their decision to focus on cartilage solutions and today’s orthopedic startup environment.

Numerous emergent products employ 3D printing and biomaterials. Why did you decide to pursue cartilage replacement and repair?

Dr. Holmes: Cartilage degeneration is an issue that virtually everyone will experience in their lifetime. It is a clinically relevant problem that needs to be addressed adequately for patients. The clinical standard is still mitigation and delay. Can you stop the degeneration, or can you slow it down to the point where someone may not need a knee replacement? Cartilage degeneration has huge long-term health implications. This also addresses the care of younger folks. The sports medicine market is growing 8% annually and is primarily driven by knee treatments.

From a technical standpoint, cartilage repair is elusive. In a purely academic setting, it continues to be a very challenging but exciting technical problem.

It was the confluence of those two reasons. You need good science to solve the problem, but once you put in the effort and time to solve it, there is a big opportunity and a big need for patients.

How would you describe your Chondrograft technology?

Dr. Holmes: There are two things I ascribe to it. First, is the newness of its material and approach. Many cartilage implants are repackaged or repurposed technologies that failed on the first attempt at development or commercialization, or they were used in a certain way and then repurposed for cartilage resurfacing. Our technology truly is new material.

Additionally, many companies have used 3D printing to create a more viable suspension for live cells. That’s not what we’re doing. Our application of 3D printing as a better core structure for cartilage has not been done before, to my knowledge.

Second, in terms of surgical workflow, our Chondrograft is less invasive, meaning that surgeons apply it arthroscopically while removing less healthy tissue. The 3D-printed structure also allows for flexible forming and molding of the implant. While it has a defined and mechanically stable shape, surgeons can still bend it and apply it through an incision or a working channel. The surgeons I talk to care about being able to move the implant through a fully arthroscopic workflow. Companies continually fail to address that factor, and it boggles my mind.

We aren’t seeding the technology with a cell or tissue sample. It’s an off-the-shelf product that surgeons can grab and use as they want, which hasn’t yet been done effectively.

We’ve developed a technology and a packaging that checks all the boxes, and you need to check all the boxes to gain adoption.

Do you see this as a platform technology?

Dr. Holmes: Absolutely. Looking at other large joints, lesions occur in the ankle, hip and shoulder. There are also opportunities to continue to tailor the project. We’ve received interest from investors in small joint extremities, hand and wrist procedures, and foot surgery. I also think there’s an opportunity for soft tissue reconstruction in the craniomaxillofacial space.

Where are you in the commercialization process?

Dr. Holmes: We are in the preclinical phase, but plan to conduct our first-in-human clinical trial this year. We’re in the process of setting up and working with the clinical sites.

We are a PMA device, so we’re looking at a long pathway to get to market. But again, there’s a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. There’s a large, well-validated need for this technology within the sports medicine niche.

We have always engaged heavily with the clinical community, even before we founded the company. We’re confident that our product will be adopted after the arduous journey of PMA clinical trials.

What else are you focusing on in 2023?

Dr. Holmes: We are looking at an international go-to-market strategy so that when we get to the pivotal trial stage, we can potentially fold in activities for a CE Mark or pursue indications in Australia and East Asia. Our first-in-human procedure will be in Australia. We’re really thinking critically about our strategy and ways we can maximize the pivotal trial to secure international indications.

We continue our development work on platform applications. We also plan additional R&D work to look at other products from the base material and from a 3D-printed approach.

Finally, we seek to maximize clinical delivery. A first-in-human study is very focused and controlled, but we want to have a tool set or kit in place. We’re working on developing that and having it ready for the pivotal trial.

Who will be your competitors, once you get to the market?

Dr. Holmes: Our device offers a lower-cost, off-the-shelf opportunity. Ultimately, our main competitor is surgical technique. We want to replace microfracture knee surgery as the go-to standard of care.

In terms of other more invasive techniques, cadaveric allografting is loosely considered the gold standard. There are only around 10,000 performed each year, but that’s probably the most widely done implant procedure that we’re looking to compete with. There are also cell therapy products that culture or enrich live cells in implantable materials.

No one has locked up this market with an effective product that physicians like using.

Ultimately, we’re looking at being able to treat half a million patients a year. There are 700,000 knee arthroscopies performed each year and, excluding microfracture procedures, about 25,000 corrective procedures involve an implant. Our technology is designed to deliver better clinical outcomes. Having a truly commoditized implant, both in terms of ease of use and cost, will allow that six-figure group of patients to benefit.

What is the current status of the startup environment? Are you raising money?

Dr. Holmes: It’s an interesting time. There’s a lot of doom and gloom. The data trends are encouraging, though. Series As finished up the year flat. We just started raising our Series A to fund the first-in-human trial, and we are in the sweet spot of the right stage to deal with the economic conditions.

Also, a lot of the market downturn was due to therapeutics and pharmaceuticals. Medical device companies are always at a huge funding disadvantage, but med device deals increased during the pandemic and have remained constant. We are in a good position to weather current and future market conditions.

Raising money is challenging regardless of the economic situation. I assume having a novel technology helps your efforts.

Dr. Holmes: It’s clear that there’s a big clinical need and a hungry customer base. When I’m talking to an investor, they almost always say, ‘I know someone who just had a joint replacement,’ or ‘I just had a joint replacement,’ or ‘I’ve had one of your competitors’ products and I was a failed case, so now I’m really interested in your product.’

People’s knees don’t stop wearing out because of fluctuations in the stock market. That has always been our motivation and continues to be our motivation. We’re not losing steam.

Cartilage repair and replacement is an underserved niche in the sports medicine market that could provide substantial opportunity for newcomers. Nanochon is one startup that plans to target the market with an off-the-shelf 3D-printed biomaterial device.

Nanochon describes its Chondrograft as “a sturdy medical advancement that is one part...

Cartilage repair and replacement is an underserved niche in the sports medicine market that could provide substantial opportunity for newcomers. Nanochon is one startup that plans to target the market with an off-the-shelf 3D-printed biomaterial device.

Nanochon describes its Chondrograft as “a sturdy medical advancement that is one part orthopedic load-bearing implant, one part tissue growth scaffold and completely revolutionary.” The company is focused on developing a nylon-based 3D-printed implant that easily integrates into a surgeon’s workflow without adding steps like cell seeding.

“We’re estimating a $2 billion target market in the U.S. annually, specifically for the sports medicine application,” said Benjamin Holmes, Ph.D., CEO of Nanochon. He noted the company is targeting younger, more active patients with knee cartilage damage or degeneration.

Dr. Holmes and CTO Nathan Castro, Ph.D., co-founded Nanochon in 2016. Their Chondrograft is an FDA premarket approval (PMA) device, with which they hope to bring to market in 2027.

We spoke with Dr. Holmes about Nanochon’s technology, their decision to focus on cartilage solutions and today’s orthopedic startup environment.

Numerous emergent products employ 3D printing and biomaterials. Why did you decide to pursue cartilage replacement and repair?

Dr. Holmes: Cartilage degeneration is an issue that virtually everyone will experience in their lifetime. It is a clinically relevant problem that needs to be addressed adequately for patients. The clinical standard is still mitigation and delay. Can you stop the degeneration, or can you slow it down to the point where someone may not need a knee replacement? Cartilage degeneration has huge long-term health implications. This also addresses the care of younger folks. The sports medicine market is growing 8% annually and is primarily driven by knee treatments.

From a technical standpoint, cartilage repair is elusive. In a purely academic setting, it continues to be a very challenging but exciting technical problem.

It was the confluence of those two reasons. You need good science to solve the problem, but once you put in the effort and time to solve it, there is a big opportunity and a big need for patients.

How would you describe your Chondrograft technology?

Dr. Holmes: There are two things I ascribe to it. First, is the newness of its material and approach. Many cartilage implants are repackaged or repurposed technologies that failed on the first attempt at development or commercialization, or they were used in a certain way and then repurposed for cartilage resurfacing. Our technology truly is new material.

Additionally, many companies have used 3D printing to create a more viable suspension for live cells. That’s not what we’re doing. Our application of 3D printing as a better core structure for cartilage has not been done before, to my knowledge.

Second, in terms of surgical workflow, our Chondrograft is less invasive, meaning that surgeons apply it arthroscopically while removing less healthy tissue. The 3D-printed structure also allows for flexible forming and molding of the implant. While it has a defined and mechanically stable shape, surgeons can still bend it and apply it through an incision or a working channel. The surgeons I talk to care about being able to move the implant through a fully arthroscopic workflow. Companies continually fail to address that factor, and it boggles my mind.

We aren’t seeding the technology with a cell or tissue sample. It’s an off-the-shelf product that surgeons can grab and use as they want, which hasn’t yet been done effectively.

We’ve developed a technology and a packaging that checks all the boxes, and you need to check all the boxes to gain adoption.

Do you see this as a platform technology?

Dr. Holmes: Absolutely. Looking at other large joints, lesions occur in the ankle, hip and shoulder. There are also opportunities to continue to tailor the project. We’ve received interest from investors in small joint extremities, hand and wrist procedures, and foot surgery. I also think there’s an opportunity for soft tissue reconstruction in the craniomaxillofacial space.

Where are you in the commercialization process?

Dr. Holmes: We are in the preclinical phase, but plan to conduct our first-in-human clinical trial this year. We’re in the process of setting up and working with the clinical sites.

We are a PMA device, so we’re looking at a long pathway to get to market. But again, there’s a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. There’s a large, well-validated need for this technology within the sports medicine niche.

We have always engaged heavily with the clinical community, even before we founded the company. We’re confident that our product will be adopted after the arduous journey of PMA clinical trials.

What else are you focusing on in 2023?

Dr. Holmes: We are looking at an international go-to-market strategy so that when we get to the pivotal trial stage, we can potentially fold in activities for a CE Mark or pursue indications in Australia and East Asia. Our first-in-human procedure will be in Australia. We’re really thinking critically about our strategy and ways we can maximize the pivotal trial to secure international indications.

We continue our development work on platform applications. We also plan additional R&D work to look at other products from the base material and from a 3D-printed approach.

Finally, we seek to maximize clinical delivery. A first-in-human study is very focused and controlled, but we want to have a tool set or kit in place. We’re working on developing that and having it ready for the pivotal trial.

Who will be your competitors, once you get to the market?

Dr. Holmes: Our device offers a lower-cost, off-the-shelf opportunity. Ultimately, our main competitor is surgical technique. We want to replace microfracture knee surgery as the go-to standard of care.

In terms of other more invasive techniques, cadaveric allografting is loosely considered the gold standard. There are only around 10,000 performed each year, but that’s probably the most widely done implant procedure that we’re looking to compete with. There are also cell therapy products that culture or enrich live cells in implantable materials.

No one has locked up this market with an effective product that physicians like using.

Ultimately, we’re looking at being able to treat half a million patients a year. There are 700,000 knee arthroscopies performed each year and, excluding microfracture procedures, about 25,000 corrective procedures involve an implant. Our technology is designed to deliver better clinical outcomes. Having a truly commoditized implant, both in terms of ease of use and cost, will allow that six-figure group of patients to benefit.

What is the current status of the startup environment? Are you raising money?

Dr. Holmes: It’s an interesting time. There’s a lot of doom and gloom. The data trends are encouraging, though. Series As finished up the year flat. We just started raising our Series A to fund the first-in-human trial, and we are in the sweet spot of the right stage to deal with the economic conditions.

Also, a lot of the market downturn was due to therapeutics and pharmaceuticals. Medical device companies are always at a huge funding disadvantage, but med device deals increased during the pandemic and have remained constant. We are in a good position to weather current and future market conditions.

Raising money is challenging regardless of the economic situation. I assume having a novel technology helps your efforts.

Dr. Holmes: It’s clear that there’s a big clinical need and a hungry customer base. When I’m talking to an investor, they almost always say, ‘I know someone who just had a joint replacement,’ or ‘I just had a joint replacement,’ or ‘I’ve had one of your competitors’ products and I was a failed case, so now I’m really interested in your product.’

People’s knees don’t stop wearing out because of fluctuations in the stock market. That has always been our motivation and continues to be our motivation. We’re not losing steam.

You are out of free articles for this month

Subscribe as a Guest for $0 and unlock a total of 5 articles per month.

You are out of five articles for this month

Subscribe as an Executive Member for access to unlimited articles, THE ORTHOPAEDIC INDUSTRY ANNUAL REPORT and more.

CL

Carolyn LaWell is ORTHOWORLD's Chief Content Officer. She joined ORTHOWORLD in 2012 to oversee its editorial and industry education. She previously served in editor roles at B2B magazines and newspapers.