Copy to clipboard

Copy to clipboard

As a sports medicine surgeon, Jacqueline Brady, M.D., understands the physical and emotional blow that a patient faces when they tear their ACL, let alone retear it. “To have an ACL surgery fail is an absolute mental health hit,” she said.

Dr. Brady specializes in ligament instability and injuries in the shoulder and knee at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), where she is Associate Residency Program Director and Surgical Director of Sports Medicine. She is also a team physician for Portland State University.

Her interests in conducting research and caring for athletes intersect in seeking to identify innovative technologies and surgical techniques that will return sports medicine patients to their active lifestyles. She said it’s also important to “ethically ask questions about the use of new implants.”

Dr. Brady is the co-principal investigator of the Bridge Registry, which follows more than 240 patients across nine sites of care who received the BEAR (Bridge-Enhanced ACL Restoration) Implant commercialized by Miach Orthopaedics.

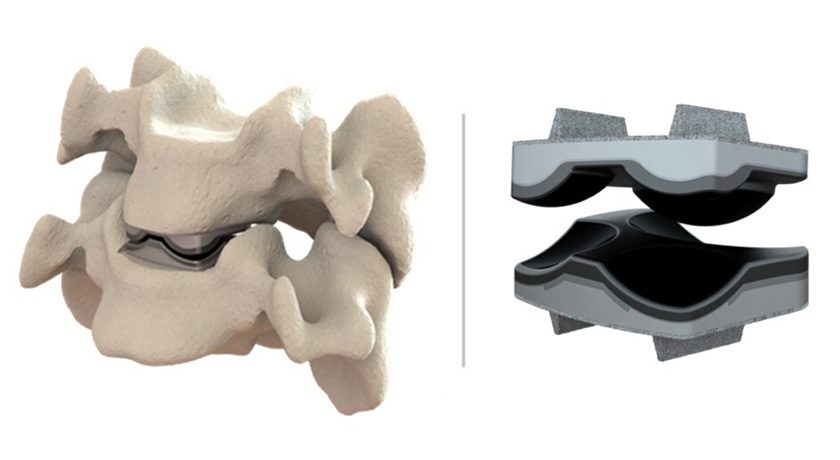

The BEAR Implant received FDA De Novo approval in late 2020 and was noted as the first technology to clinically demonstrate that it enables healing or restoration of a torn ACL. The implant is made of decellularized Type 1 bovine collagen, which is injected with the patient’s own blood and secured via suture to bridge the gap between the torn ends of the ACL.

“The bovine collagen has great platelet inhibition and adhesion properties to preserve the fibrin/platelet clot that makes the ligament heal,” Dr. Brady said. By eight weeks, the implant is replaced by native cells, collagen and blood vessels, and over time, the new tissue remodels and becomes stronger.

BEAR is designed to restore the natural anatomy and function of the knee and does not require a second surgical procedure to remove a healthy tendon graft from another part of the patient’s leg or the use of a donor tendon.

Dr. Brady said that the ability to restore the ACL and patient outcomes thus far are extremely promising. She expects positive data will encourage more surgeons to adopt the technology. The BEAR Implant has already changed her approach to caring for patients with ACL tears. “This is real disruptive technology in the best of ways,” she said.

In March, Miach Orthopaedics received FDA 510(k) clearance to expand the indication of the BEAR Implant to include adolescents and children, as well as to treat partial ACL tears. Previously, the implant was only indicated for adults and complete ACL ruptures. Further, the implant no longer needs to be implanted within the first 50 days after the ligament tear. The new emphasis is on the quality of the remaining tissue.

Changes in Technique

More than 5,000 patients had been treated with the BEAR Implant as of March. However, with any new technology, questions remain as surgeons perfect the technique and patients begin their rehabilitation journey. Clinical data, whether through studies or registries, helps answer the “nitty gritty” questions about implant placement and patient selection, Dr. Brady said.

“The goal of the Bridge Registry is to follow these patients as a cohort to study real-world use of the implant,” she said. “Importantly, the surgeons don’t need to adhere to the original surgical technique.”

Dr. Brady admitted that she is a rule follower. After learning a new surgical technique, she feels the need to follow the steps as she learned them. That’s not always practical in the O.R. Surgeons often take the simplest, fastest and least morbid route to accomplish a successful surgical procedure for the patient, she said.

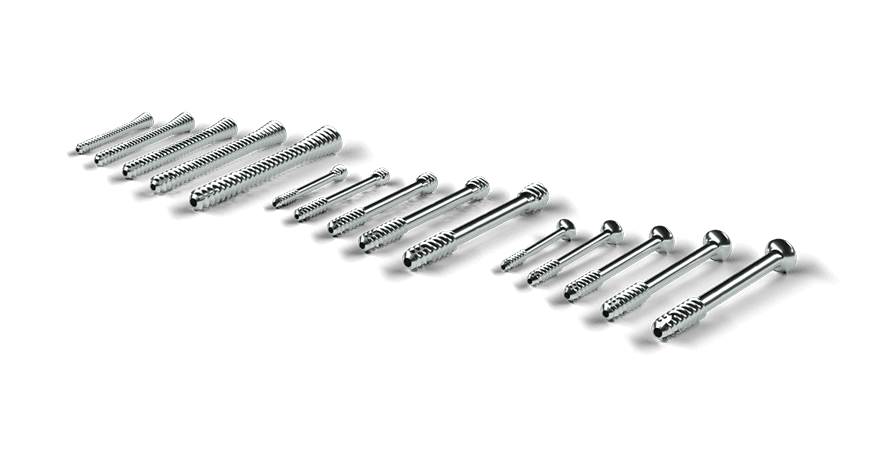

Not surprisingly, data from the Bridge Registry show that surgeons began modifying the recommended technique as they performed more procedures with the BEAR implant. Outcomes data is being analyzed to determine what leads to the best results. Should femoral or tibial buttons be used instead of anchors? Should stronger sutures be used instead of absorbable ones or suture tape?

Dr. Brady said that, most importantly, there was no difference in safety outcomes between the modified and original techniques used to place the BEAR implant. After one year, the overall reoperation rate in 96 patients was 8.4% and included two retears. The BEAR II study, which followed the traditional technique, had a retear rate of about 14%.

The different surgical modifications can make for an apples-to-oranges comparison, Dr. Brady said. “It’s hard to say that this adjustment worked better than that one, but we are increasingly suspicious that the modifications are leading to a low failure rate,” she said. “For example, we wonder if using a stronger suture is better. We just can’t prove it yet.”

The most compelling data Dr. Brady is watching for are the rates of failure, development of osteoarthritis and patterns in return to motion. She also noted that if the BEAR implant improves patient outcomes in the highest risk group, it could provide even more clarification as to how to treat a more normal population.

Continuous Monitoring

While Dr. Brady is focused on analyzing the results of patients in the registry, she’s also closely watching the wealth of clinical data Miach Orthopaedics is collecting in other studies. Patients in three clinical studies continue to be monitored to gather long-term data. The company also recently announced it finished enrollment in its BEAR MOON study, a 150-patient randomized controlled clinical trial comparing the BEAR Implant to the gold standard: autograft bone-patellar tendon-bone (BPTB) ACL reconstruction.

With a handful of multicenter studies being conducted, it’s important to parse out the data from the different groups, Dr. Brady said. “If we don’t expect the suture to break over time, then we need to ask a lot of questions about where it is placed and how it fixed,” she added. “I’m encouraged by the results. It’s still important to ask really thorough questions to optimize how we use the implant.”

As a sports medicine surgeon, Jacqueline Brady, M.D., understands the physical and emotional blow that a patient faces when they tear their ACL, let alone retear it. “To have an ACL surgery fail is an absolute mental health hit,” she said.

Dr. Brady specializes in ligament instability and injuries in the shoulder and knee at Oregon Health...

As a sports medicine surgeon, Jacqueline Brady, M.D., understands the physical and emotional blow that a patient faces when they tear their ACL, let alone retear it. “To have an ACL surgery fail is an absolute mental health hit,” she said.

Dr. Brady specializes in ligament instability and injuries in the shoulder and knee at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), where she is Associate Residency Program Director and Surgical Director of Sports Medicine. She is also a team physician for Portland State University.

Her interests in conducting research and caring for athletes intersect in seeking to identify innovative technologies and surgical techniques that will return sports medicine patients to their active lifestyles. She said it’s also important to “ethically ask questions about the use of new implants.”

Dr. Brady is the co-principal investigator of the Bridge Registry, which follows more than 240 patients across nine sites of care who received the BEAR (Bridge-Enhanced ACL Restoration) Implant commercialized by Miach Orthopaedics.

The BEAR Implant received FDA De Novo approval in late 2020 and was noted as the first technology to clinically demonstrate that it enables healing or restoration of a torn ACL. The implant is made of decellularized Type 1 bovine collagen, which is injected with the patient’s own blood and secured via suture to bridge the gap between the torn ends of the ACL.

“The bovine collagen has great platelet inhibition and adhesion properties to preserve the fibrin/platelet clot that makes the ligament heal,” Dr. Brady said. By eight weeks, the implant is replaced by native cells, collagen and blood vessels, and over time, the new tissue remodels and becomes stronger.

BEAR is designed to restore the natural anatomy and function of the knee and does not require a second surgical procedure to remove a healthy tendon graft from another part of the patient’s leg or the use of a donor tendon.

Dr. Brady said that the ability to restore the ACL and patient outcomes thus far are extremely promising. She expects positive data will encourage more surgeons to adopt the technology. The BEAR Implant has already changed her approach to caring for patients with ACL tears. “This is real disruptive technology in the best of ways,” she said.

In March, Miach Orthopaedics received FDA 510(k) clearance to expand the indication of the BEAR Implant to include adolescents and children, as well as to treat partial ACL tears. Previously, the implant was only indicated for adults and complete ACL ruptures. Further, the implant no longer needs to be implanted within the first 50 days after the ligament tear. The new emphasis is on the quality of the remaining tissue.

Changes in Technique

More than 5,000 patients had been treated with the BEAR Implant as of March. However, with any new technology, questions remain as surgeons perfect the technique and patients begin their rehabilitation journey. Clinical data, whether through studies or registries, helps answer the “nitty gritty” questions about implant placement and patient selection, Dr. Brady said.

“The goal of the Bridge Registry is to follow these patients as a cohort to study real-world use of the implant,” she said. “Importantly, the surgeons don’t need to adhere to the original surgical technique.”

Dr. Brady admitted that she is a rule follower. After learning a new surgical technique, she feels the need to follow the steps as she learned them. That’s not always practical in the O.R. Surgeons often take the simplest, fastest and least morbid route to accomplish a successful surgical procedure for the patient, she said.

Not surprisingly, data from the Bridge Registry show that surgeons began modifying the recommended technique as they performed more procedures with the BEAR implant. Outcomes data is being analyzed to determine what leads to the best results. Should femoral or tibial buttons be used instead of anchors? Should stronger sutures be used instead of absorbable ones or suture tape?

Dr. Brady said that, most importantly, there was no difference in safety outcomes between the modified and original techniques used to place the BEAR implant. After one year, the overall reoperation rate in 96 patients was 8.4% and included two retears. The BEAR II study, which followed the traditional technique, had a retear rate of about 14%.

The different surgical modifications can make for an apples-to-oranges comparison, Dr. Brady said. “It’s hard to say that this adjustment worked better than that one, but we are increasingly suspicious that the modifications are leading to a low failure rate,” she said. “For example, we wonder if using a stronger suture is better. We just can’t prove it yet.”

The most compelling data Dr. Brady is watching for are the rates of failure, development of osteoarthritis and patterns in return to motion. She also noted that if the BEAR implant improves patient outcomes in the highest risk group, it could provide even more clarification as to how to treat a more normal population.

Continuous Monitoring

While Dr. Brady is focused on analyzing the results of patients in the registry, she’s also closely watching the wealth of clinical data Miach Orthopaedics is collecting in other studies. Patients in three clinical studies continue to be monitored to gather long-term data. The company also recently announced it finished enrollment in its BEAR MOON study, a 150-patient randomized controlled clinical trial comparing the BEAR Implant to the gold standard: autograft bone-patellar tendon-bone (BPTB) ACL reconstruction.

With a handful of multicenter studies being conducted, it’s important to parse out the data from the different groups, Dr. Brady said. “If we don’t expect the suture to break over time, then we need to ask a lot of questions about where it is placed and how it fixed,” she added. “I’m encouraged by the results. It’s still important to ask really thorough questions to optimize how we use the implant.”

You’ve reached your limit.

We’re glad you’re finding value in our content — and we’d love for you to keep going.

Subscribe now for unlimited access to orthopedic business intelligence.

CL

Carolyn LaWell is ORTHOWORLD's Chief Content Officer. She joined ORTHOWORLD in 2012 to oversee its editorial and industry education. She previously served in editor roles at B2B magazines and newspapers.