Copy to clipboard

Copy to clipboard

Orthopaedics, specifically the way that our bones have evolved over millennia, has garnered global attention in recent months due to research by sports medicine surgeon Paul Monk, M.D., and a team at the Nuffield Department of Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences at University of Oxford.

The BBC to newspapers in India to tech trade journals have covered the research, bringing attention to the work of surgeons, device companies and what we can do as individuals to preserve our joints.

The creation of the Trillennium Man gained interest because the research team worked with the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C., the Natural History Museum in London and the zoology department at Oxford to make 3D CT reconstructions of 224 bone specimens. The 3D scans of knees, hips and shoulders were compiled into morphs that allow you to see how the shapes of our joints have changed over the last 350 million years, and what they might look like 4,000 years from now. You can view the morphs at chromaticinnovation.com/trillennium-man.

Using a generic, one-dimensional model of a human, Monk identified reasons for several trends that may impact joint reconstruction product development today and in the future.

Perhaps the most striking trend was that seen in the hip. As we have moved from a quadrupedal to bipedal locomotion strategy, we see more bone in the femoral neck, and the head/neck ratio is rapidly trending towards that of arthritic patients.

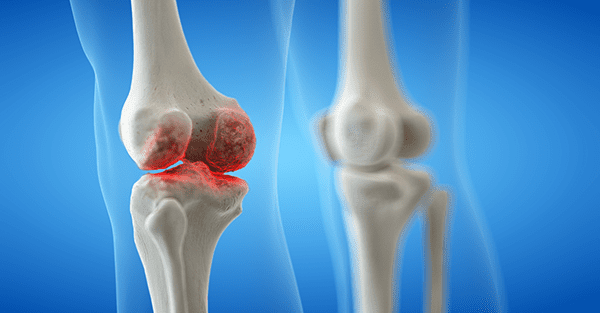

In the shoulder, as we’ve gone from a quadrupedal to bipedal position, the pitch of the acromion has flattened and moved more anteriorly. “We know that tendons pass through that gap, and now there is less space for them to move,” Monk says. “That might explain why more and more people are presenting with impingement symptoms. We’ve had similar insights from other joints, including the knee.”

“We hope findings such as these will help inform the next generation of orthopaedic interventions,” Monk says. “This research highlights the musculoskeletal factors that are changing dramatically. It highlights which disease patterns need to be corrected, and provides other insights such as which parts of a knee prosthesis are the most important, and perhaps which parts of the arthroscopic procedure in the shoulder we should be addressing.”

Since the Trillennium Man was published in late 2016, Monk has received requests for other bones, and the hope is to print the remaining bones.

The research idea came about from Monk questioning why patient after patient presented with similar musculoskeletal disorders—shoulder impingement, hip arthritis, knee dislocation. He believed that clues from our past could offer predictions as to how these conditions will evolve.

When asked what he has learned and his thoughts on the greatest evolution in orthopaedics during his professional career, Monk, who is currently based in New Zealand, mentioned the rise of custom implants.

“We’re moving from an era where ‘one shape fits all’ toward a personalized approach, a patient-specific solution. I have a feeling that will be one of the big changes during my career,” he says. “There will be more preparatory time and effort spent before we arrive in the OR to do the procedure. 3D prints of individual joints are already preoperative adjuncts. Routinely, I think we will see an extra cycle of engineering that occurs before we arrive in the OR, so that the operative solution is available by the time we start the operation. That is where this research can make its impact.”

Orthopaedics, specifically the way that our bones have evolved over millennia, has garnered global attention in recent months due to research by sports medicine surgeon Paul Monk, M.D., and a team at the Nuffield Department of Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences at University of Oxford.

The BBC to newspapers in India to tech...

Orthopaedics, specifically the way that our bones have evolved over millennia, has garnered global attention in recent months due to research by sports medicine surgeon Paul Monk, M.D., and a team at the Nuffield Department of Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences at University of Oxford.

The BBC to newspapers in India to tech trade journals have covered the research, bringing attention to the work of surgeons, device companies and what we can do as individuals to preserve our joints.

The creation of the Trillennium Man gained interest because the research team worked with the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C., the Natural History Museum in London and the zoology department at Oxford to make 3D CT reconstructions of 224 bone specimens. The 3D scans of knees, hips and shoulders were compiled into morphs that allow you to see how the shapes of our joints have changed over the last 350 million years, and what they might look like 4,000 years from now. You can view the morphs at chromaticinnovation.com/trillennium-man.

Using a generic, one-dimensional model of a human, Monk identified reasons for several trends that may impact joint reconstruction product development today and in the future.

Perhaps the most striking trend was that seen in the hip. As we have moved from a quadrupedal to bipedal locomotion strategy, we see more bone in the femoral neck, and the head/neck ratio is rapidly trending towards that of arthritic patients.

In the shoulder, as we’ve gone from a quadrupedal to bipedal position, the pitch of the acromion has flattened and moved more anteriorly. “We know that tendons pass through that gap, and now there is less space for them to move,” Monk says. “That might explain why more and more people are presenting with impingement symptoms. We’ve had similar insights from other joints, including the knee.”

“We hope findings such as these will help inform the next generation of orthopaedic interventions,” Monk says. “This research highlights the musculoskeletal factors that are changing dramatically. It highlights which disease patterns need to be corrected, and provides other insights such as which parts of a knee prosthesis are the most important, and perhaps which parts of the arthroscopic procedure in the shoulder we should be addressing.”

Since the Trillennium Man was published in late 2016, Monk has received requests for other bones, and the hope is to print the remaining bones.

The research idea came about from Monk questioning why patient after patient presented with similar musculoskeletal disorders—shoulder impingement, hip arthritis, knee dislocation. He believed that clues from our past could offer predictions as to how these conditions will evolve.

When asked what he has learned and his thoughts on the greatest evolution in orthopaedics during his professional career, Monk, who is currently based in New Zealand, mentioned the rise of custom implants.

“We’re moving from an era where ‘one shape fits all’ toward a personalized approach, a patient-specific solution. I have a feeling that will be one of the big changes during my career,” he says. “There will be more preparatory time and effort spent before we arrive in the OR to do the procedure. 3D prints of individual joints are already preoperative adjuncts. Routinely, I think we will see an extra cycle of engineering that occurs before we arrive in the OR, so that the operative solution is available by the time we start the operation. That is where this research can make its impact.”

You are out of free articles for this month

Subscribe as a Guest for $0 and unlock a total of 5 articles per month.

You are out of five articles for this month

Subscribe as an Executive Member for access to unlimited articles, THE ORTHOPAEDIC INDUSTRY ANNUAL REPORT and more.

CL

Carolyn LaWell is ORTHOWORLD's Chief Content Officer. She joined ORTHOWORLD in 2012 to oversee its editorial and industry education. She previously served in editor roles at B2B magazines and newspapers.