Copy to clipboard

Copy to clipboard

When Natalie Mesnier, M.D., first heard about minimally invasive bunion surgery at the major medical meetings about 10 years ago, she was skeptical. “I figured this was just a fad and would be debunked shortly,” she said. “But then it struck me that performing minimally invasive bunion repair could solve many problems we often see, like excess postoperative swelling and patient frustration with lengthy non-weight-bearing periods.”

The more Dr. Mesnier looked into minimally invasive bunion surgery, the more excited she became. At the time, minimally invasive solutions were so far ahead of the curve that they hadn’t yet received FDA clearance. She decided to seek her initial training in Spain, where the necessary surgical tools were available to learn new techniques.

Fast-forward a decade and Dr. Mesnier’s practice has been transformed, with the vast majority of her bunion repair cases today being minimally invasive. Now an acknowledged expert, she has trained many other surgeons in minimally invasive surgical techniques.

Seen as an underserved procedure by orthopedic companies, bunion repair has recently received significant attention in the form of new products and dedicated sales efforts that are shaping the foot and ankle market. It’s considered one of the fastest-growing sectors in orthopedics and a ripe procedure for minimally invasive solutions.

A fellowship-trained orthopedic surgeon, Dr. Mesnier is a subspecialist in orthopedic foot and ankle reconstruction at Multnomah Orthopaedic Clinic in Portland, Oregon. We spoke with her about her interests in minimally invasive techniques and technologies.

How has bunion surgery evolved in recent years?

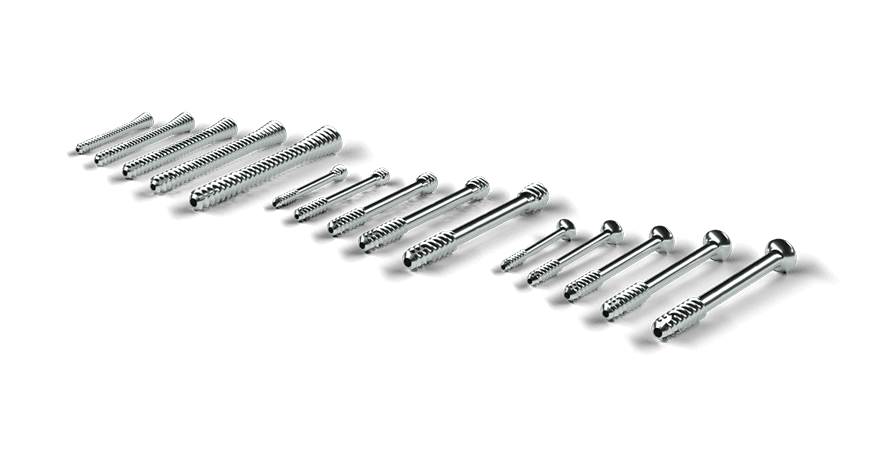

Dr. Mesnier: The key developments are improvements to the tools that we use to correct bunions, not so much the surgery itself. Instead of the sagittal saw we all trained on, with 40,000 RPM, we now have bone-cutting tools that are the size of a ballpoint pen’s tip. Instead of swiping with a broad swath, they rotate at 6,000 RPM. By being low torque, the new tools can brush up against softer tissues like nerves and muscles without cutting or injuring them.

My incisions are about 2mm, so the damage to the surrounding tissues is minimal. This has resulted in much less tethering, and patients have greater range of motion. We’re doing the bone cut outside the joint instead of the traditional cut inside the joint, so stiffness is much less of an issue.

How has minimally invasive bunion surgery impacted patient recovery and outcomes?

Dr. Mesnier: The number one impact by far is reduced pain. Patients used to need a lot of narcotics after having traditional bunion repair, but now most post-op pain is controlled with acetaminophen and ibuprofen. It’s a dramatic change in trajectory, especially with newer implants that allow early weight-bearing. Patients can mobilize much more quickly, which results in less joint stiffness and quicker return to activities.

Patients can also get back into their shoes more quickly, which is a huge benefit. With traditional surgery, there was often a mismatch between when I told them their mobility was good enough to hit the gym and when they could get their foot into a shoe. If you can’t get your foot into your athletic shoes, you’re not going to the gym, no matter what I say. Every aspect of health and function has improved with the approaches we’re doing today.

How steep is the learning curve to adopt minimally invasive surgery? Are there tools or tricks you’ve found to make the curve less steep?

Dr. Mesnier: There is a learning curve, but the key is it’s the same surgery, open or closed, it’s just a different tool. So, it’s a matter of mastering that tool by taking cadaver courses, which are widely available. I tell surgeons they can always start by making a slightly larger incision, maybe instead of a 2 mm incision, it’s 3 or 4 mm. There’s nothing wrong with that.

Surgeons should start with the incision size that they feel comfortable with, but use the minimally invasive tool. They can practice hand movements and watch what the tool does and how it feels. They’re still using fluoroscopy, so they’re not flying blind. Yes, the patient will still have a big incision, but with decreased risk of thermal injury and other postoperative issues. The next time surgeons perform the surgery, they might be more comfortable going smaller and smaller until reaching that 2mm incision.

What would you say to a colleague who remains skeptical of learning minimally invasive bunion repair?

Dr. Mesnier: To surgeons who are in training now or recently trained, minimally invasive techniques are what they know. We’re hearing that many residents and fellows are choosing programs based on whether there are faculty with a deep commitment to training in minimally invasive procedures. New surgeons don’t want to go to a program where the emphasis is on maintaining the status quo.

Has changing your focus to minimally invasive bunion surgery changed your advice to patients?

Dr. Mesnier: The conventional wisdom was always to wait until their bunions were really bad before getting the surgery. But waiting leads to secondary deformities that are harder to fix and treat than an uncomplicated bunion repair. I agreed with the conventional wisdom until about five years ago, but switching to minimally invasive procedures and seeing how much better my patients did really helped me rethink that old attitude. Let’s get past the point of forcing people to live with pain and dysfunction just because we think we should see a certain degree of impairment before feeling like it’s time to operate.

When Natalie Mesnier, M.D., first heard about minimally invasive bunion surgery at the major medical meetings about 10 years ago, she was skeptical. “I figured this was just a fad and would be debunked shortly,” she said. “But then it struck me that performing minimally invasive bunion repair could solve many problems we often see, like excess...

When Natalie Mesnier, M.D., first heard about minimally invasive bunion surgery at the major medical meetings about 10 years ago, she was skeptical. “I figured this was just a fad and would be debunked shortly,” she said. “But then it struck me that performing minimally invasive bunion repair could solve many problems we often see, like excess postoperative swelling and patient frustration with lengthy non-weight-bearing periods.”

The more Dr. Mesnier looked into minimally invasive bunion surgery, the more excited she became. At the time, minimally invasive solutions were so far ahead of the curve that they hadn’t yet received FDA clearance. She decided to seek her initial training in Spain, where the necessary surgical tools were available to learn new techniques.

Fast-forward a decade and Dr. Mesnier’s practice has been transformed, with the vast majority of her bunion repair cases today being minimally invasive. Now an acknowledged expert, she has trained many other surgeons in minimally invasive surgical techniques.

Seen as an underserved procedure by orthopedic companies, bunion repair has recently received significant attention in the form of new products and dedicated sales efforts that are shaping the foot and ankle market. It’s considered one of the fastest-growing sectors in orthopedics and a ripe procedure for minimally invasive solutions.

A fellowship-trained orthopedic surgeon, Dr. Mesnier is a subspecialist in orthopedic foot and ankle reconstruction at Multnomah Orthopaedic Clinic in Portland, Oregon. We spoke with her about her interests in minimally invasive techniques and technologies.

How has bunion surgery evolved in recent years?

Dr. Mesnier: The key developments are improvements to the tools that we use to correct bunions, not so much the surgery itself. Instead of the sagittal saw we all trained on, with 40,000 RPM, we now have bone-cutting tools that are the size of a ballpoint pen’s tip. Instead of swiping with a broad swath, they rotate at 6,000 RPM. By being low torque, the new tools can brush up against softer tissues like nerves and muscles without cutting or injuring them.

My incisions are about 2mm, so the damage to the surrounding tissues is minimal. This has resulted in much less tethering, and patients have greater range of motion. We’re doing the bone cut outside the joint instead of the traditional cut inside the joint, so stiffness is much less of an issue.

How has minimally invasive bunion surgery impacted patient recovery and outcomes?

Dr. Mesnier: The number one impact by far is reduced pain. Patients used to need a lot of narcotics after having traditional bunion repair, but now most post-op pain is controlled with acetaminophen and ibuprofen. It’s a dramatic change in trajectory, especially with newer implants that allow early weight-bearing. Patients can mobilize much more quickly, which results in less joint stiffness and quicker return to activities.

Patients can also get back into their shoes more quickly, which is a huge benefit. With traditional surgery, there was often a mismatch between when I told them their mobility was good enough to hit the gym and when they could get their foot into a shoe. If you can’t get your foot into your athletic shoes, you’re not going to the gym, no matter what I say. Every aspect of health and function has improved with the approaches we’re doing today.

How steep is the learning curve to adopt minimally invasive surgery? Are there tools or tricks you’ve found to make the curve less steep?

Dr. Mesnier: There is a learning curve, but the key is it’s the same surgery, open or closed, it’s just a different tool. So, it’s a matter of mastering that tool by taking cadaver courses, which are widely available. I tell surgeons they can always start by making a slightly larger incision, maybe instead of a 2 mm incision, it’s 3 or 4 mm. There’s nothing wrong with that.

Surgeons should start with the incision size that they feel comfortable with, but use the minimally invasive tool. They can practice hand movements and watch what the tool does and how it feels. They’re still using fluoroscopy, so they’re not flying blind. Yes, the patient will still have a big incision, but with decreased risk of thermal injury and other postoperative issues. The next time surgeons perform the surgery, they might be more comfortable going smaller and smaller until reaching that 2mm incision.

What would you say to a colleague who remains skeptical of learning minimally invasive bunion repair?

Dr. Mesnier: To surgeons who are in training now or recently trained, minimally invasive techniques are what they know. We’re hearing that many residents and fellows are choosing programs based on whether there are faculty with a deep commitment to training in minimally invasive procedures. New surgeons don’t want to go to a program where the emphasis is on maintaining the status quo.

Has changing your focus to minimally invasive bunion surgery changed your advice to patients?

Dr. Mesnier: The conventional wisdom was always to wait until their bunions were really bad before getting the surgery. But waiting leads to secondary deformities that are harder to fix and treat than an uncomplicated bunion repair. I agreed with the conventional wisdom until about five years ago, but switching to minimally invasive procedures and seeing how much better my patients did really helped me rethink that old attitude. Let’s get past the point of forcing people to live with pain and dysfunction just because we think we should see a certain degree of impairment before feeling like it’s time to operate.

You are out of free articles for this month

Subscribe as a Guest for $0 and unlock a total of 5 articles per month.

You are out of five articles for this month

Subscribe as an Executive Member for access to unlimited articles, THE ORTHOPAEDIC INDUSTRY ANNUAL REPORT and more.

DL

Darcy Lewis Darcy Lewis is an ORTHOWORLD Contributing Editor